Jennifer’s Academic Journey

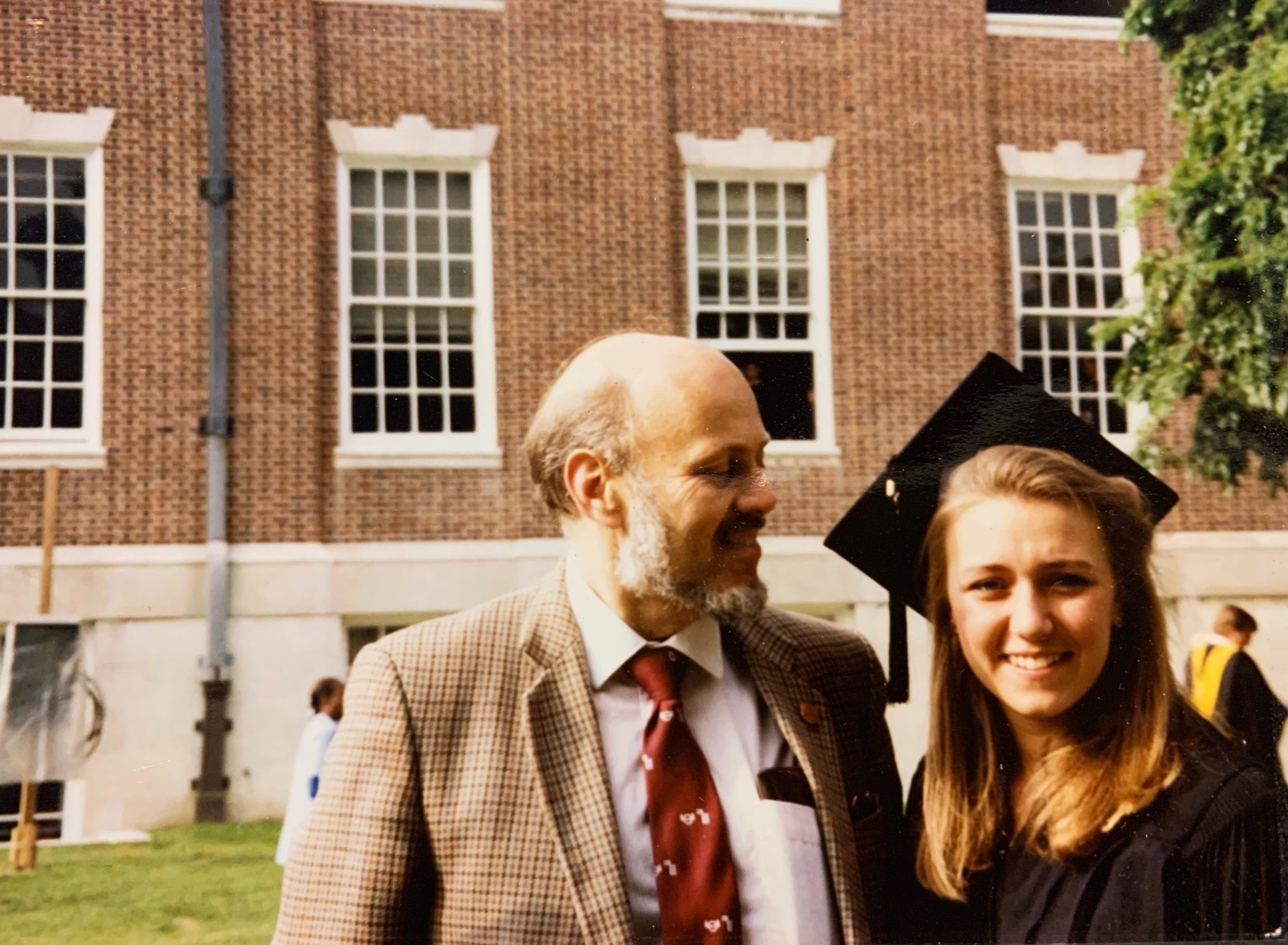

My dad and me at my college graduation from Johns Hopkins

I may have received my bachelors degree and PhD over three decades ago, but I’ve never really left college. In fact, I got quite an early start too…

My first college home was when I was just four years old, at Webb Institute of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering, where my father spent his career as a math professor. Webb is a unique place. It is tiny, with only about a hundred students, and offers a full-tuition scholarship to every undergraduate student. It is a school most people have never heard of, yet it appears on various college ranking lists, such as the schools with the highest endowment per student and most highly selective. Located on a stunning 26-acre campus on the Long Island Sound in New York, Webb is a perfect place for students to learn to build boats–and for a professor’s young children to explore and collect “sea” glass. As a child, my favorite days were when I’d take the long car ride from my home in Rockland County, NY, about 10 miles north of New York City, across the George Washington Bridge, the Bronx, and Queens, to Webb. I would sit in the front row of my dad’s lectures, coloring, or, when I was older, wait for him in his office during his lecture. I remember him meeting with his students and helping them with their math. His female students were my first role models for women engineers. My brothers and I ate breakfast and lunch with the students in the dining hall and on special occasions, in the faculty dining room with my father and his colleagues. We wore t-shirts with “Half a ship, half a grade” written on them and explored the buildings containing towing tanks that students used for their naval architecture labs. Years later, I was married at Webb on a hot July day as the sun set over the Long Island Sound.

My second college home was the Homewood campus of Johns Hopkins University, where I received my undergraduate degree. For four years, I walked the pathways of the beautiful campus and quads, a green space amidst the larger urban city of Baltimore. It wasn’t an easy place. Founded by Daniel Coit Gilman as the first research university in the United States after the German model of higher education, Johns Hopkins is a place that demands independence. At the time, undergraduates were housed on campus for only one year, after which we moved into off-campus apartments. Hopkins is the premed capital of the world, and academics are serious. There was no grade inflation. One relief was we received only pass-fail grades at the end of the first semester, a system designed to allow us to get our academic bearings.

When I matriculated, the institution had been co-ed for a scant fifteen years, the undergraduate population as a whole was approximately a third female, and I was routinely the only female student in my engineering classes or one of just a few. The few female engineers I overlapped with were often mixed up by others (at this point, I must shout out to Sue, Carole, Nancy, and Rochelle. Carole, how many times were we confused for each other?) Despite the challenges, I thrived during my four years at Hopkins. When considering the “Big Six” College Experiences linked to life-long success, I had them all. I was fortunate to have had faculty that inspired, encouraged, and mentored me. I walked on to the swim team, joined a sorority, tutored Baltimore elementary school children, and worked in Admissions giving campus tours. I did research in a professor’s lab on two different projects for several years. One summer, I also worked in the seismology department at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University. A highlight of my undergraduate time was studying abroad in Paris for a semester. I graduated from Hopkins with a BS in Electrical Engineering and was well prepared for graduate school.

My third college home was Carnegie Mellon University, where I spent five years teaching and researching while earning an MS and Ph.D. in Electrical and Computer Engineering. Carnegie Mellon was founded by Andrew Carnegie, one of America’s greatest industrialists, and is well-known for educating students who learn strong skills valued by industry. This more practical approach was a valuable balance to my research-based Hopkins education. At Hopkins, I learned to prove things. At CMU, I learned to build them. I used machines new to me and collected data on hardware platforms I had built rather than simulated environments. I gained many important skills and confidence in my identity as a “real” engineer.

My mom and me when I received my PhD at Carnegie Mellon

It, too, wasn’t an easy place. Out of 220 graduate students in the ECE department, only 20 were women. Of 60 faculty members, there was only one female professor, and she was denied tenure while I was there. The machine shop where I worked had pinups hanging on the walls - a bikini-clad woman looked down on me as I used the lathe. When I went in advance to meet with the professors who would serve as my three qualifying examiners, one of them told me, as he puffed on his pipe, that if I failed the exam, I should go home and bake cookies for the rest of my life (I passed the three-hour grueling oral exam!) I was determined and prevailed. Andrew Carnegie was Scottish, and CMU had many Scottish influences. Every official event included triumphant bagpiping. Sometimes as I walked on campus to class, I’d be lucky to hear one of the bagpipers practicing, the sounds muted from a distance. Today, I am transported back to CMU whenever I hear bagpipes. And I’ve worn my academic regalia accented with tartan plaid with pride at the many official college and university events I’ve participated in in the years that followed. I am grateful for the ways in which my CMU education benefits me to this day.

Next, beautiful Wellesley College became my fourth college home for 21 years. As a nontenure track (teaching) professor of computer science for the first 14 years, I carved out a life of balance as I raised three daughters. I reveled in Wellesley’s mission to educate women who will make a difference in the world and was professionally fulfilled by teaching and learning from my talented students. And, with a flexible schedule and summers off, I could be the mother I wanted to be to my children. Moreover, my entire family benefited from being a part of the Wellesley College community. My children often joined me for ordinary work days. They would sit in the front row of my lectures coloring and, when older, roam the campus, swing on the long swings under the majestic trees outside the Chapel, explore the Arboretum or greenhouses, and walk around Lake Waban. They’d also join me for special holiday events, like the annual Cirque du CS celebration of student work and faculty-student cookie-baking parties in the dorms (we would draw circuits in icing on the cookies!) In this context, my daughters met extraordinary, inspiring students.

When my youngest daughter became old enough to attend full-day school, I transitioned to a class dean role at the College, enabling me to focus more on the parts of my job that I valued the most: mentoring and advising students. On my last day in the department, my CS students left construction-paper footprints leading to my office, each with a handwritten note thanking me for how I made my mark on their time as their professor. As a class dean, I continued educating students in a different way. My role was to help students achieve their academic and personal goals, access the available resources, and manage obstacles and challenges. In this work, I broadened and deepened my perspective on aspects of the student experience that I had not been fully aware of before. It was a privilege to impact individual students meaningfully. I proudly led my class at Commencement Exercises, celebrating my students as they walked across the stage. Privately, my heart swelled with joy and pride for those who may not have made it without my help. I also enjoyed the opportunities I had to impact students as a whole, for instance, by setting up double degree and certificate engineering programs with MIT and Olin College of Engineering and hiring Wellesley’s first engineering professor.

I am currently the Dean of Academic Advising and Undergraduate Studies for the School of Engineering at Tufts University, my fifth and current college home. To be fair, Tufts was my oldest daughter’s home first. She had just finished her first year when I started in my role. I often call Tufts a “Goldilocks” school, meaning it is “just right.” It is a student-centered research university with bright undergraduate students and challenging academics yet a culture of balance. Many people would call it perfect in size and location. It is small for a university and provides a beautiful campus with easy access to Boston. Tufts undergraduate academic programs are stellar and comprehensive and offered through its Schools of Engineering, Arts and Sciences, and the Museum of Fine Arts. My daughter thrived at Tufts and had all the big six college experiences. And I’m thriving too. I bring all my professional experiences and expertise – STEM and advising – to bear in my work. I continue to enjoy connecting meaningfully with individual students and helping them achieve their academic and personal goals. However, in my leadership role, I have a more expansive purview, overseeing all the undergraduate academic policies, processes, and curriculum for the School of Engineering, and a much bigger “seat at the table” when decisions are made. So I have far more opportunities to impact students through institutional change. I’ve led changes to policies to address student mental health needs as Chair of Tufts President Monaco’s Mental Health Task Force, created new engineering study abroad and co-op programs, and revamped the undergraduate engineering requirements to be more flexible. I also steered academic decisions, policies, and processes during the pandemic. Throughout, I always center students and their needs. The work is exciting.

An academic life is rewarding. My favorite day of the year is the first day of the academic year each fall. The campus buzzes with excitement, promise, and potential as all the students return. When walking across the quad, the energy is palpable and infectious. It is a privilege to be surrounded by young adults as they develop their identities and to participate in this process. It is a gift to engage with the hopeful optimism of youth regularly and to have even a minor role in their realizing their dreams. I remember an international Wellesley College student once saying to me, “One day, I will either be president of my country or this college.” And I believed her. I still do. I can’t wait to see which! I believe I learn as much from my students as I teach them. I'm grateful for all the students who've shared their lives with me and all the lessons I've learned from their doing so.

I began counseling high school students to apply to college about a dozen years ago. My two roles, college dean and independent educational consultant, complement and enhance each other naturally. Every time I sit with a student in my office at Tufts (or before Tufts, Wellesley,) I am reminded of all the investment of the student and their family to arrive at a place like Tufts and Wellesley. I know exactly what it takes to prepare a competitive application for highly-selective institutions. Likewise, I work with high school students every day as they chart their paths to college and, as I do so, I guide them with a deep awareness of what awaits them in college. I have my finger on the pulse of higher education. I know what questions they should be asking and how to guide them to find answers to these questions. After all, I am on a college campus supporting undergraduate students every day. And I have over twenty-five years of experience doing so to draw on. It is a privilege to be a part of their journey to college.

Today, I rejoice in the professional life I’ve created for myself. I could never have scripted my career nor predicted its path. My early idea had been to be a professor, but I realized that the role would only partially satisfy me. At the start of my career, I had no idea my current roles existed. I found my way to where I am now by asking myself hard questions and doing my best to answer them. What do I love? What am I good at? What will positively contribute to the world? What can I be paid for? Authentically answering these questions led me to where I am today. I've learned through my experiences that we each have significant power to create things for ourselves - our future. I did this at each stage of my career. And I encourage this thinking in my students. I regularly challenge my students to dream big, envision their future, and see what they can create for themselves! And I support and celebrate them as they do.

Many people supported and celebrated me as I made my academic journey and built my career. However, it was my father who modeled an academic life for me, encouraged me to study engineering, told me never to let anyone tell me that girls could not do math, helped me with my math homework until I went to college, and was so unabashedly proud of my successes at every step. I would not be where I am today without him. Thank you, dad.